Extract

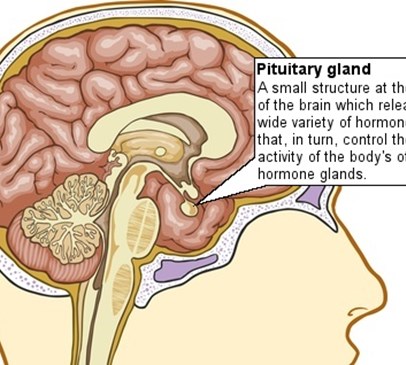

After many decades of being considered simply a clinical endocrinology "curiosity", the long-term endocrine consequences of traumatic brain injury (TBI) have in the past few years been the subject of resurgent interest. First reported almost 100 years ago,1 chronic pituitary dysfunction following a head injury was originally thought to be a rare occurrence.2 This viewpoint has been challenged by recent research on adult survivors of severe brain injury. These studies variously report the prevalence of pituitary hormone deficiencies to be between 23% and 69%.3-5 It is clear from these studies that one or any number of hypothalamic-pituitary hormone axes may be impaired in the chronic phase following head injury, with the growth hormone (GH; 10-33%), adrenal (5-23%) and gonadal axes (8-30%) apparently the most vulnerable to problems. Further clinical complexity is also evident from prospective, longitudinal observations, which suggest that for many head-injury survivors pituitary hormone dysfunction may not develop until at least 6 to 12 months after TBI, whereas, in others deficiencies can be transient and resolve spontaneously during the year after the trauma.5 6 Morbidity following moderate-to-severe head injury is high, and many of the chronic problems and symptoms reported in this group of patients (eg, fatigue, poor concentration and depression) are common to the clinical phenotype associated with hypopituitarism.

Reference

Acerini, CL. (2008) Head-injury-induced pituitary dysfunction. An old curiosity rediscovered, Archives of Disease in Childhood 93(5): 364-5.

Back