Executive dysfunction after brain injury

Executive function is the name for a collection of thinking skills that we use when solving problems, making decisions, planning and completing tasks, and reflecting on our activity. Impairment of executive functions is common after acquired brain injury and has a profound effect on many aspects of everyday life.

This page explains:

- What are executive functions?

- Which part of the brain is involved?

- What is executive dysfunction?

- Symptoms of executive dysfunction

- Professional help for executive dysfunction

- Coping strategies for brain injury survivors

- A carer's point of view

What are executive functions?

'Executive function' involves skills such as planning, motivation, multi-tasking, flexible thinking, monitoring performance, memory, self-awareness, and detecting and correcting mistakes.

We rely on many of these executive function skills on a daily basis, such as to cook a meal, follow a conversation, interact with others, work, study and plan our day, among other activities.

Which part of the brain controls executive functions?

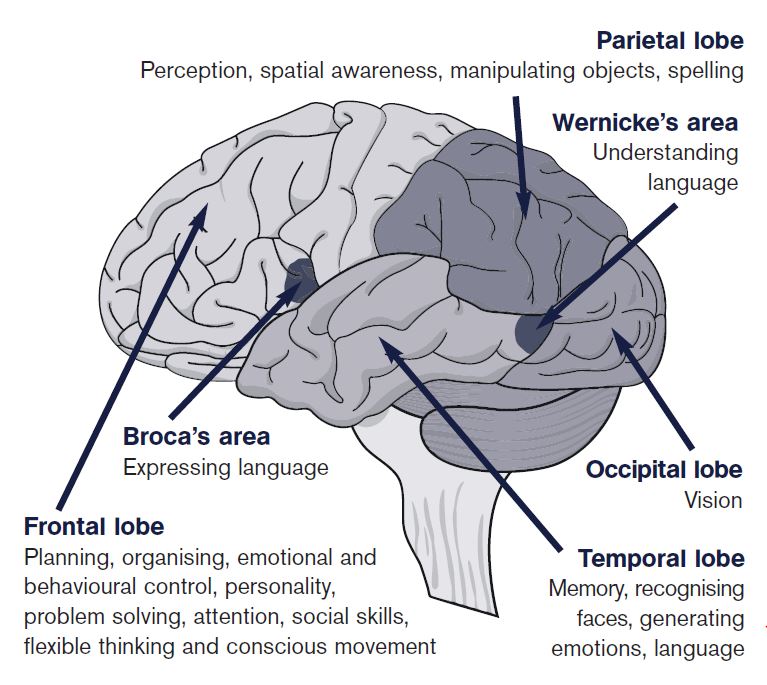

Executive function skills are processed in a part of the brain called the prefrontal cortex. Other parts of the brain closely connected to the prefrontal cortex are also involved.

Unfortunately, the prefrontal cortex's positioning in the brain (at the front, directly behind the forehead), in the frontal lobe, makes it a common site of injury.

The diagram below shows their location:

The frontal lobes can be damaged by any form of acquired brain injury, such as stroke, tumour, encephalitis and meningitis. They are particularly vulnerable to traumatic brain injury, due to their location at the front of the brain and their large size. Even a blow to the back of the head can cause frontal lobe injury because the brain is knocked back and forth in the skull and the frontal lobes bang against bony ridges above the eyes.

What is executive dysfunction?

People with injury to their prefrontal cortex can have difficulties with their executive function skills - when this happens, they are said to have executive dysfunction.

Executive dysfunction is also sometimes referred to as 'frontal lobe problems' or 'dysexecutive syndrome'.

The most common effects of executive dysfunction are summarised below:

Difficulties with motivation and initiation

A survivor may lose their sense of 'get up and go', making it difficult for them to start or complete tasks. This may be mistaken by others for laziness or disinterest. For example, a survivor may frequently be reminded about needing to book an appointment, but even though they intend to do it, they don't get started on it so it doesn't get done.

Difficulties with organisation

A survivor may struggle with making and sticking to plans. Thinking through the steps to get things done may be difficult for them. For example, a survivor may be unable to keep track of appointments and frequently get these muddled up.

Difficulties with flexible thinking

Adapting or changing behaviour, or switching between tasks may be difficult, as the survivor may become stuck or fixed on certain information or behaviours - this is called 'rigid thinking'. For example, thinking to lower the heat if food is unexpectedly cooking too quickly.

Difficulties with problem-solving

Thinking through problems and forming solutions may be difficult for the survivor. It may also be difficult for them to anticipate the consequences of their decisions. For example, a survivor may be unsure of what steps to take if they have lost their bank card.

Impulsivity

A survivor may act too quickly and impulsively without fully thinking through the possible consequences, for example spending most of their pay-cheque on something without considering the bills that need to be paid later.

Difficulties with planning

Thinking ahead and going through the various steps to complete an activity may be more difficult for the survivor. For example, it may be confusing for a survivor to follow the various steps needed to arrange and book a holiday.

It may be difficult to identify exactly which areas of executive dysfunction are impaired, and often more than one skill is affected. The symptoms can also range from subtle effects, which only close friends and family members may notice, to extreme and problematic behaviour.

The effects of executive dysfunction on day-to-day life

Executive dysfunction can cause problems with aspects of day-to-day functioning, such as:

- Starting or finishing tasks

- Planning ahead

- Making decisions

- Thinking through problems and forming solutions

- Using alternative solutions if needed

- Behaving appropriately and controlling emotions such as anger

- Interacting with others

As these effects are not visible, it is sometimes difficult for others to recognise or understand them. This can be upsetting, frustrating or embarrassing for some brain injury survivors. On the other hand, some brain injury survivors may themselves be unaware of their executive dysfunction - they may not have insight into the impact of their brain injury. Executive dysfunction can also cause family and friends to become upset, embarrassed or frustrated, especially if the survivor refuses help to deal with their effects.

Returning to work or education may be particularly difficult for survivors with executive dysfunction, as we rely on many of our executive function skills for working and studying, such as multi-tasking, organisation and motivation. Struggling to prioritise, make decisions and complete tasks can also make life difficult.

As well as having difficulties with managing day-to-day life, a brain injury survivor with executive dysfunction may find themselves in challenging situations. For example, they may encounter financial problems if they have impulsively spent more money than they ought to have, or they may accidentally get into trouble with the police.

Headway's Brain Injury Identity Card can help survivors who find themselves in these sorts of difficult situations.

Professional help for executive dysfunction

Professionals called clinical neuropsychologists can help with identifying areas of executive dysfunction that may be causing difficulties. This may be done by asking the brain injury survivor to complete neuropsychological tests. There are many different types of neuropsychological tests, with some broadly testing cognitive skills while others explore specific aspects of cognition in more detail.

More information about the support that clinical neuropsychologists can offer is available in our factsheet Executive dysfunction after brain injury, available in the Information Library.

Coping strategies for brain injury survivors

The following tips are general suggestions for coping with various aspects of executive dysfunction. They do not replace clinical guidance.

Motivation

- Try to identify the reasons why a certain task is important to you. Sometimes it can help us to complete something if we are emotionally motivated to do it.

- Make a note of things that need to be done and stick it in a prominent place, such as writing on a brightly coloured post-it note that you are likely to notice regularly. You could cross items off as you complete them. This can help to stay organised and motivated, while also offering a positive sense of achievement.

- Set alarms to try and prompt yourself to begin an activity.

- Set times and dates by when you aim to complete an activity and make a note of these, for example on a calendar.

- Consider rewarding yourself each time you complete a task. The rewards can be something simple, such as treating yourself to a snack you enjoy or saving an episode of a program you like to watch until you have completed the task that needs to be done.

Organising

- Keep a list of things that you need to do or things that you need to remember, or use a diary to organise your time.

- Set yourself timers and reminders for things that you need to do.

- Use a filing system to keep important papers, emails, etc, organised, for example keeping a separate, labelled folder for hospital letters.

- Try to plan things in advance where possible, so that you have enough time to organise yourself.

- Try to keep things that you regularly use or things that you regularly take out with you, such as your keys or your mobile phone, in one single place.

- When you are in the middle of a task that has lots of steps (such as cooking a meal), try to pause regularly and take a moment to think. Ask yourself: 'What am I doing just now? Where am I up to in my plan? Should I still be doing this task or should I have moved onto another task?' Remember: STOP-THINK.

Flexible thinking

- Where possible, try to make back-up plans in advance and write these down so that you are prepared if you need to change your plans. This can help a lot if you are under time pressure during a task and have to change plans at short notice.

- Try to break larger tasks up into different stages so that you can focus on one at a time. For instance, cooking one part of a dinner and then keeping it warm in an oven while focusing on cooking the next part of it.

- If you need to complete multiple activities at the same time, set a reminder so that you are prompted to swap between them.

- Talk through plans with others so that they can help you to think about situations that might involve a change of plan and how you will deal with this.

Planning

- Use a step-by-step approach, dividing activities into manageable 'chunks' and make a list of each step. For example, if you are planning a holiday, you could make lists with separate headings such as 'things to pack', 'agencies to contact', 'travel dates', etc. If you are completing your activity with someone, such as a friend or a colleague, ask them to look over the list to make sure you have not left any steps out.

- Use checklists, and tick off each part of the activity you have completed. This may help you to stay on track.

- Allow yourself plenty of time to plan activities and record your plans, using things such as calendars, diaries, alarms, mobile phones, etc, to make notes, lists and set reminders.

- Mentally rehearse your plans.

- Discuss your plans for the rest of the day with others; they may be able to help you to stay on track with your planned activities.

- Prepare a weekly routine for tasks like shopping, washing and tidying the house. Knowing, for example, that Monday is a shopping day, may make it easier to plan ahead for shopping, such as preparing a shopping list.

- Try to make back-up plans in advance so that you are better prepared if problems come up.

For more tips, see our factsheet Executive dysfunction after brain injury, available from the Information Library.

Executive dysfunction from a carer's point of view

Caring for a person with executive deficits can be a full-time job and living with personality and behaviour changes in a relative or friend can be very distressing.

Problems that carers may experience include:

- Stress, anxiety or depression

- Increased responsibility

- Strained relationships

- Reduced communication with partner

- Restricted leisure/social life

- Reduced sexual and emotional intimacy with a partner

- Feeling tired and frustrated

It is important for family members, carers and friends to access support for their practical and emotional needs. Input from a rehabilitation team can help, and some people find peer support groups for carers useful. Headway's groups and branches offer valuable support for both survivors and family members. It is also important to see a GP, who will be able to refer to local counselling and therapy services where they are available.

For further information see the Headway booklet Caring for someone with a brain injury, which can be obtained free-of-charge from the Headway helpline, or visit the 'Caring' section for more information. The helpline can also provide support and refer to local groups and branches.

7 signs of executive dysfunction after brain injury

Executive dysfunction is a term used to collectively describe impairment in the 'executive functions'.

Find out moreCognitive effects of brain injury

The cognitive effects of a brain injury include issues with speed of thought, memory, understanding, concentration, solving problems, using language and more.

Find out moreEmotional effects of brain injury

Everyone who has had a brain injury can be left with some changes in emotional reaction. These can be some of the most difficult for the individual concerned and their family to deal with.

Find out moreBehavioural effects of brain injury

Behavioural changes after brain injury are many and varied. Get more information on these common effects of brain injury.

Find out more9 ways to help with planning problems after brain injury

Find out more10 ways to cope with depression after brain injury

Find out moreMemory problems

Memory is easily affected by brain injury because there are several structures within the brain that are involved in memory, and injury to any of these parts can impair memory performance.

Find out moreConclusion

The frontal lobes are commonly affected by acquired brain injury. Damage to the frontal lobes is likely to cause symptoms which are collectively termed executive dysfunction.

The diverse ways executive difficulties present themselves mean that assessment and rehabilitation are not straightforward. However, with appropriate rehabilitation and the use of coping strategies, many people can make good recoveries and learn to manage their difficulties.